OFFER: A BRAND NEW SERIES AND 2 FREEBIES FOR YOU!

Grab my new series, "Secrets and Courtships of the Regency", and get 2 FREE novels as a gift! Have a look here!

Prologue

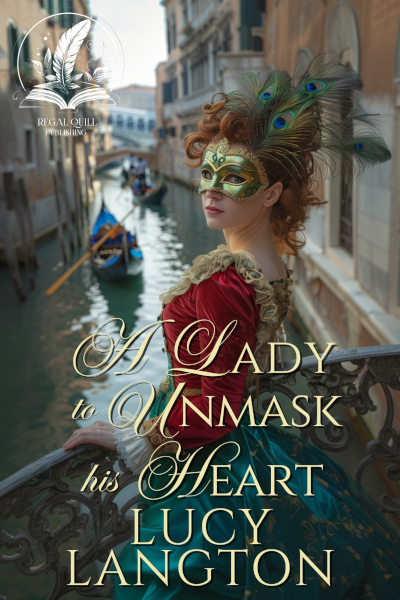

Venice, 1818

The night in Venice was bathed in candlelight.

Isabella Nightingale had never known air so heavy with music, perfume, and promise. It shimmered, it swayed—it draped itself over her like a silk shawl, perfumed with roses and salt.

The Palazzo Thornton, with its arched windows and balustraded terrace overlooking the Grand Canal, pulsed like a heart at the center of revelry. Every chandelier was a constellation—Murano glass dripping with stars, each facet catching flame and flinging it across the ballroom in molten scatterings.

The air was gilded, and for once, so was she.

Her auburn hair was like tamed fire under her pinned hairdo, a few loose curls framing her face elegantly. Her emerald-green eyes peered through her mask—an elaborate colombina trimmed in emerald and gold, its edges flaring with peacock feathers—seemed to grant her another face, a bolder one. Beneath it, her skin prickled with excitement that was part fear, part delight.

If it weren’t for the mask, she would have been a spitting image of her mother in her youth.

She had been in Venice for merely a week, yet it already felt like a dream stitched together by water and light. The gondolas gliding below the Palazzo murmured songs she did not yet understand.

And tonight—amid the foreign voices, the fluttering silks, the crescendo of violins—she felt a quickening she could neither name nor suppress.

Her uncle, Lord Reginald Nightingale, had declared the ridotto a harmless amusement.

“The Thorntons are English, my dear,” he had said, “and as respectable a family as any exiled from Bath.” But even his stateliness faltered before the spectacle. Her brother Albinus, dark-eyed and solemn as their father, lingered near the refreshment table, looking as though he’d prefer the company of a ledger.

Cousin George, by contrast, had already melted into the crowd, laughing too loudly, whispering too much. And Isabella—eighteen, restless, and suddenly alive—had drifted toward the dance floor as if gravity itself were calling her there.

The orchestra struck a sprightly note. The room rearranged itself into pairs and patterns, the floor a living tapestry of satin and lace.

When a gentleman in a silver bauta mask bowed before her, his hand extended with a confidence bordering on insolence, she hesitated for only a heartbeat before laying her gloved fingers in his.

“May I?”

He did not introduce himself; he merely inclined his head, and she—startled by the steadiness of those chocolate brown eyes through that faceless mask—let herself be drawn into the swirling current of the contradanza.

Her eyes twinkled as she nodded demurely, letting the rhythm claim them.

His tall and athletic frame moved with measured ease; as if he had studied her long before that evening. Every step she took, he mirrored with uncanny dexterity. When she turned, his hand was there, poised to catch hers before she even lifted it.

When the dance called for a change of partner, he reclaimed her as though he had always known she would return. Around them, laughter and chatter blurred into an indistinct hum, the way the sea hums in one’s ear after a long swim. The violins seemed to answer only to their movements.

Isabella’s pulse quickened—not merely from the pace of the dance, but from the strange, magnetic surety in his touch. She could not see his eyes, but she felt them—felt the weight of his attention as if it were heat.

And she, who had spent years obeying the decorum of drawing rooms and governesses, found herself thrilling to the small rebellion of it.

Her mind betrayed her with a sudden, absurd thought: He knows me. Not by name, not by family, not by virtue—but by rhythm, by the silent vocabulary of steps and breath.

When the music faded, and the room dissolved into applause and bowing, he leaned closer—close enough that she caught the faint scent of bergamot and something subtler beneath it, something like cedarwood after rain.

“The stars above the terrace,” he murmured in a low, unmistakably English voice, “are particularly beautiful tonight.”

The words slipped into her ear like a secret. They were not scandalous enough to provoke outrage, nor polite enough to dismiss as harmless. They hovered, perfectly poised between gallantry and daring. She should have turned away. She knew she should have. Yet her curiosity bloomed like a forbidden flower.

Before she could frame a reply, he bowed again and disappeared into the throng.

Isabella lingered, her heart ticking unevenly beneath her stays. The chandeliers suddenly seemed too bright, the laughter too shrill. She felt as though she had been awakened from something—something she wanted to fall back into.

She found herself moving toward the terrace almost without will, the peacock feathers trembling faintly with each step.

The night air outside was a reprieve—a cool hand laid upon a flushed cheek. Beyond the marble balustrade stretched the Grand Canal, black as spilled ink, its surface trembling with fractured reflections of lanterns and stars.

Gondoliers called softly to one another, their voices carrying like lullabies over the water. Around her, small knots of guests stood murmuring, their laughter drifting like perfume.

And there—by the shadow of a column—stood the man in the bauta.

He turned when she approached, and the faint light caught his profile as he lifted the mask away.

Leonard Lymington.

Her breath caught, a strange, delighted recognition unfurling within her.

Two days before, she had met him at Caffè Florian, beneath the painted ceilings that made even conversation feel like theatre. Her uncle had introduced The Duke of Wiltshire and his son Lord Leonard Lymington to her and Albinus. The duke had been grand and cautious, the sort of man who weighed every word as though it might tip a scale.

Lord Lymington had looked at her with the same active interest with which he seemed to look at everything: the frescoes, the paintings, the steaming coffee that stained his fingers with warmth.

She remembered their conversation with unusual clarity. How the men had argued about a Venetian painter whose new work had scandalized collectors—whether art should reflect life as it was or embellish it into what it ought to be.

Leonard had turned to her then, asking, “And you, Lady Isabella? Should art flatter or accuse?”

She had not expected to be asked. And she still remembered her reply, the boldness of it surprising even herself: “Neither. It should remind.”

He had smiled—not mockingly, but as though she had said something he had been waiting to hear.

Now, on the terrace, beneath the same moon that glittered over Florian’s square two nights past, that smile returned.

“I hoped it was you,” he said softly. “When I saw the peacock feathers, I thought—no one else would dare.”

Isabella felt her pulse stumble. “I did not imagine you would attend the Thorntons’ ridotto.”

“Nor did I imagine you would dance,” he said. “You seemed the type to study the steps first.”

A flush crept along her throat, half embarrassment, half thrill. “You presume much for a man whose name I have known but two days.”

“Perhaps,” he said, tilting his head slightly, “but Venice does that; it dissolves propriety like salt in water.”

His words, softly spoken yet laden with suggestion, carried the faint hum of something larger—an understanding, perhaps, or an invitation she dared not name.

Around them, the night murmured: oars dipping, laughter echoing from the ballroom, a woman’s fan fluttering open like wings.

Isabella glanced back toward the lighted hall, where the dance continued without her. The air outside smelled of water and wax, and something faintly metallic—like the taste of longing itself.

“You are bold, Lord Lymington,” she said at last, trying to sound composed.

“And you,” he replied, “are braver than you realize.”

Her heart thumped once, hard.

Perhaps it was the mask, the music, or the impossible magic of Venice itself but standing there, beneath that crescent moon, she felt the strange certainty that her life had just shifted, subtly, irrevocably, like the tide turning beneath the city.

She looked away, her gaze drifting over the glittering water, but her mind remained fixed on him—on the echo of his voice, the warmth of his hand that still lingered against her palm, and the dangerous sweetness of being seen.

Lord Lymington lingered a moment before speaking, his mask now resting against his gloved fingers like a discarded pretense. The faint light from the ballroom windows gilded his hair, catching in pale threads that shimmered as he turned toward her.

“I confess,” he said, his tone low but unguarded, “I attended this evening in the hope of finding you again.”

Isabella’s breath wavered. For a fleeting instant she felt the pulse of her heart in her throat, that quickened flutter of disbelief that made the world sharpen into color.

The violins from within drifted out onto the terrace, muffled by distance but still alive, like the faint beating of some collective heart.

“You came… because of me?” she managed, her voice softer than she intended, as though afraid the words might scatter if spoken too loudly.

“Entirely because of you,” he replied, without hesitation. His candor, unadorned by the polite evasions of society, startled her more than any flattery could have.

Isabella lowered her gaze, feeling the rush of warmth that crept beneath her mask. “We have only met twice.”

“Once at Florian’s, and again tonight. Twice is sometimes all that is needed,” he said. “Venice is a city that collapses time. It takes a day to lose oneself here, an hour to forget who one was before, and a single moment to… wish differently.”

She could not help but release a quiet laugh. It sounded unfamiliar to her own ears, lighter, freer, as if the very air conspired to make her unrecognizable to herself.

“You speak like one of those painters at Florian’s,” she said. “All sentiment and grand illusion.”

“Perhaps,” he conceded, smiling. “But tell me, Lady Isabella, has Venice not made a dreamer of you as well?”

Her answer hesitated on the edge of thought. Perhaps it has. The city had bewitched her from the moment she arrived: its mirrored waters, labyrinthine alleys, and its scent of decay and divinity intertwined.

Every shadow seemed painted; every silence, orchestrated. Even at that moment, standing beside him beneath that crescent moon, she felt as though they were figures trapped within a canvas, caught forever between one heartbeat and the next.

She looked toward the balustrade, where the faint shimmer of lantern light trembled across the canal.

“It has,” she admitted quietly. “But Venice does not love its dreamers for long. The water remembers too much.”

Lord Lymington tilted his head. “And yet you know its moods as though you’ve studied it all your life.”

Isabella smiled faintly.

“I listen,” she said. “That’s all. The city speaks, if one has the patience to hear. The bridges are its bones, the piazzas its breath. The light changes like thought itself.”

He regarded her, a flicker of astonishment beneath his poise.

“You astonish me,” he said after a pause. “Most young women I meet can scarcely distinguish a basilica from a ballroom, yet you speak of architecture as though it has a pulse.”

She lifted her eyes to him, half amused. “You assume I should not notice such things?”

“Forgive me,” he said, with a sincerity that softened his tone. “It is not what I am accustomed to.”

“Then you have been accustomed poorly.”

The retort slipped out before she could stop it. It hung between them for a moment, gleaming like the sharp edge of a jewel. Then he laughed. Quietly, but with such warmth that the tension dissolved at once.

“You are right,” he said. “I have been. You see, Lady Isabella, no one has ever challenged my mind while captivating my heart so thoroughly.”

Isabella froze at that. The word heart in a man’s mouth carried a weight it seldom did in books. In the candlelight his expression was unreadable—somewhere between admiration and confession—and she found herself looking away, her pulse quickening until it felt as though the air itself trembled with it.

For the first time since arriving at the ridotto, she became aware of her arm; a peculiar numbness had crept from her wrist upward, perhaps from the tightness of her glove. She flexed her fingers discreetly, wincing as the blood returned in sharp tingles.

“Are you unwell?” his voice softened immediately.

“It is nothing,” she said, though the faint discomfort persisted. “My glove… perhaps too tightly drawn.”

She began to unbutton it, fumbling slightly at the wrist. The ivory kid leather resisted her, reluctant to yield. He stepped closer—close enough that she could feel the heat of him through her sleeve—and offered assistance. The gesture was tender, deliberate, almost reverent.

When the glove at last came loose, she drew it away and flexed her bare fingers in the cool air. The sudden freedom was startling. Her skin looked pale, almost luminous beneath the moonlight, the faint blue of her veins visible like delicate rivers.

Lord Lymington’s gaze followed the motion, and before she could protest, he reached out and took her hand lightly, his thumb brushing the pulse that trembled beneath the skin.

“There,” he murmured. “Better?”

It was only a touch, brief and decorous, yet it sent a tremor through her that no waltz could have matched. The contact felt impossibly intimate, as though the night itself had narrowed to that single point of warmth between them.

“I believe so,” she whispered, though her voice betrayed her.

He released her slowly, almost reluctantly. “You are certain?”

“Yes,” she said, forcing steadiness she did not feel. “Though I should return before my uncle grows anxious.”

“Then allow me,” he said, and offered his arm.

They moved together toward the ballroom doors, Isabella quickly sliding her glove back on before they were subjected to the eyes of royal onlookers again,.

The threshold was high; a raised step of carved marble worn smooth by centuries of feet. When she hesitated, he steadied her hand again, guiding her across.

It was a trivial gesture, the sort every gentleman was expected to make, yet in that moment it felt monumental. Her gloved hand rested against his, and through the fine barrier of fabric she felt the electric awareness surge once more, swift and involuntary.

Isabella drew in a quiet breath. It cannot be proper to feel so much from so little, she told herself. And yet propriety, in that instant, felt like a distant country she could no longer remember how to reach.

They paused just within the doorway. The light from the chandeliers spilled around them, refracted through glass and smoke and music. The dancers still spun in golden motion, oblivious to the smaller drama unfolding at the edge of their world.

Lord Lymington turned to her, his voice lower now, almost earnest. “When I return to England,” he said, “I mean to call upon your family. Your uncle spoke warmly of your home in Sussex.”

Isabella blinked, startled by the calm certainty of his tone. “You would call upon… us?”

“If your uncle will receive me,” he said, his gaze steady. “And if you…” He paused, as though catching himself before speaking too plainly. “If you would not find it unwelcome.”

Her throat tightened. Words rose and faltered. She had known men to make gallant declarations before—poets of passing fancy, admirers of her family’s rank—but never had one spoken with this quiet gravity, this lack of performance.

There was something almost unsettling in its simplicity, like a promise uttered not for effect but because it had already been decided.

“I…” she began, but her voice trailed. She could not trust it not to tremble.

He inclined his head slightly, the faintest smile touching his lips. “Then it is settled.”

The orchestra swelled again. A new dance was beginning, ribbons and laughter rising like waves. A pair of guests swept past them into the light, the woman’s gown whispering against Isabella’s skirt.

He stepped back, his hand dropping to his side, as though the world had reclaimed him.

“I shall not detain you longer,” he said softly. “Your brother watches, and I suspect his patience is less infinite than mine.”

Isabella turned instinctively. Across the room, Albinus stood near a marble column, his expression unreadable beneath the flicker of candlelight. When she looked back, the duke was already fading into the crowd, his figure swallowed by a tide of silk and shadow.

For a long moment she stood motionless, her regloved hand still tingling, the imprint of his touch lingering like a secret against her skin. Around her, the ridotto whirled on with its brightness, its laughter, and its endless glitter.

Yet she felt apart from it, suspended in some fragile interval between heartbeat and memory. Her heart raced, but not with fear. It was something wilder, ungovernable. It was the quiet panic of possibility.

Venice had given her countless marvels in a single week: art, water, light. But as Leonard Lymington, vanished among the dancers, she knew none of it would ever compare to the dangerous wonder that had just begun to unfold.

And though she did not yet name it, she felt, with sudden clarity, that her life up until that night had been only the prelude.

Chapter Two

The music had shifted again. It was another lively contradanza rippling through the marble ballroom, like sunlight on disturbed water, but Leonard scarcely heard it. His gaze wandered over the gilded crowd, seeking a particular flash of peacock feathers among the sea of silks and masks.

Isabella Nightingale. Even her name, when thought silently, seemed to alter the air around him.

He had meant to depart hours ago. He had even reached for his cloak at one point, half-convinced that the wisest course was retreat. But then he had caught the glint of her hair beneath the chandeliers, that auburn fire defying the candlelight, and all prudence had deserted him.

Now she was nowhere to be seen.

The Palazzo Thornton was an ode to excess, a Venetian combination of color and heat. Candles burned in profusion, mirrored in every panel of Murano glass that lined the walls; perfume mingled with the faint salt from the canals drifting through open arches.

The air was crowded with laughter, the rustle of satin skirts, the polite hum of English voices made reckless by anonymity. Masks made liars of everyone; desire walked unashamed among respectability’s borrowed finery.

Leonard moved along the edge of the ballroom, scanning each dancer, each figure gliding in perfect formality. His pulse thrummed with restlessness, the same unnamable fever that had haunted him since their first conversation at Florian’s.

He had not known that a few sentences spoken over paintings could carve such a mark into his thoughts. Her laughter—low, intelligent, and unwilling to yield—had lodged itself in him like an ache.

Who would have thought it would be her presence that would grace him again that night?

Her handkerchief, pale and delicate, which was left forgotten on the terrace bench when she drew her glove off, hid inside his coat pocket. His hand crept inside his coat pocket to feel the silk of it when a hand clapped his shoulder.

“Leonard!”

He turned to find his cousin, Edward Lymington, striding toward him through the press of guests. Edward, though only a few years his senior, carried the air of a man perpetually amused by his own mischief. His hair was slightly disheveled, his smile just a fraction too wide.

“There you are,” Edward said, lowering his voice. “I have been hunting you like a bloodhound. I need a favor. An urgent one.”

Leonard regarded him warily. “Your definition of urgency tends to differ from mine.”

Edward’s eyes darted briefly toward a columned alcove where a figure in sapphire silk had just vanished behind a curtain.

“I’ve an appointment,” he murmured. “A private one. But it presents a difficulty.”

Leonard folded his arms. “Does it now?”

Edward leaned closer. “She believes I am unattached.”

Leonard arched an eyebrow. “Which would be rather awkward, considering you are betrothed to Lady Clara Wentworth back in Hampshire.”

Edward’s grin did not falter. “Quite. You see my predicament.”

“I fail to see why this involves me.”

“I need your mask,” Edward said, in a rush. “Just for an hour. The bauta conceals more of the face than mine does. And you, dear cousin, are yet unshackled by promise. If anyone should happen upon us, it will be you they think they see. You understand.”

Leonard stared at him. “You mean to borrow not only my mask but my name?”

Edward gave a careless shrug, the gesture of a man accustomed to indulgence. “Hardly theft, only temporary misdirection. You are the very model of discretion, Leonard. No one will suspect you of impropriety. Besides, what harm can there be? One lives but once.”

Leonard’s frown deepened. “And one’s honor but once lost.”

“Spare me your sermons,” Edward said lightly, though a hint of irritation flickered across his features. “I only ask for a mask, not a confession.”

Leonard hesitated. His upbringing had not prepared him for deception, however trivial. Yet the pleading urgency in his cousin’s tone and the potential for greater scandal if Edward were recognized made refusal equally perilous.

The Lymington name had endured centuries untarnished. It did not deserve to be dragged through Venetian gossip.

With visible reluctance, he removed his bauta mask—the plain white visage with its jutting jaw and smooth anonymity—and handed it over.

“I will not defend you if this folly returns to bite,” he said.

Edward’s grin brightened again. “You will not need to. I am perfectly capable of biting back.”

“That I do not doubt.”

Edward fastened the mask with practiced ease, adjusting it over his features. Beneath the pale plaster, his eyes gleamed with mischief.

“My thanks, cousin,” he said, clapping Leonard’s shoulder. “You are a man of virtue, and therefore a dangerous ally. Wish me luck.”

“Luck will not redeem you if you are caught,” Leonard muttered.

Edward only laughed—a low, rakish sound—and vanished into the glittering throng.

For a moment Leonard stood motionless, the faint echo of that laughter lingering like the aftertaste of wine gone sour. He sighed, adjusting the simple domino mask he now wore in place of the bauta.

It felt thinner, inadequate, as though he had surrendered not merely disguise but protection itself.

He resumed his search for Isabella, but the ballroom had become a labyrinth of color and motion. Everywhere, faces blurred into sameness beneath feathers and silk. The music grew louder, faster, its rhythm mocking his unease.

He passed the mirrored wall where candlelight trembled across his reflection—half-masked, half-exposed—and felt a flicker of discomfort. How easily a man could become a stranger in such surroundings. Venice thrived on illusion; it offered anonymity as both pleasure and peril.

And where was she now?

He caught himself imagining her reaction if she knew he’d lent his mask to Edward. Isabella Nightingale, sharp-tongued, bright-eyed, and too discerning by half. She would likely scold him for complicity. She would be right to.

Still, some part of him longed to see her again, if only to anchor himself. Amid all the masquerade, her presence had felt real. Terrifyingly so.

He drifted toward the musicians, scanning the dancers, the balconies, even the garden doors where couples stole air and gossip in equal measure. But there was no trace of her. Only strangers, smiling beneath their disguises, laughter rising like perfumed smoke.

Time blurred. An hour, perhaps more, slipped by in candlelight and confusion.

Then—

“Leonard!”

The voice was unmistakable. He turned to find Edward again, emerging from the direction of the gardens. His cravat hung loose, his hair disordered, a flush bright upon his cheeks. The bauta mask dangled from his hand.

“My deepest gratitude,” Edward announced, his words slightly slurred with triumph. “You have saved me from an awkward entanglement, or perhaps delivered me into one. Who can say?”

Leonard regarded him sharply. “You are flushed.”

“Exercise,” Edward said breezily. “A brisk walk among the roses. Venice inspires all manner of exertion.”

He handed back the mask, its ribbon frayed. “A word of advice, cousin, never underestimate the persuasive power of moonlight.”

Leonard took the mask but did not smile. “You might remember that moonlight does not excuse dishonor.”

Edward waved a dismissive hand. “Oh, do not look so grim. No harm done. Save, perhaps, to a lady’s sense of discretion.”

Leonard’s expression hardened. “Whose discretion?”

Edward hesitated, then shrugged as if it mattered little. “Some woman in a colombina mask… peacock feathers, I think. She appeared from nowhere, startled as a doe, and fled before I could utter a word.”

Leonard froze. The moment Edward’s careless words left his mouth—some woman with a peacock-feathered mask spotted me in the gardens and fled—the truth struck him with the precision of a blade finding the gap in armor.

Isabella. “A colombina mask with peacock feathers?” Leonard repeated.

The woman Edward spoke of could be no other. The memory of her mask, its jeweled plumage shimmering under moonlight, rose with cruel clarity. A thousand thoughts collided, each trying to claw its way to the surface.

“Yes,” Edward said, irritation creeping into his tone. “She will likely run to her companions and weave some nonsense about impropriety. Women do love their gossip, particularly when scandal smells fresh.”

She had seen Edward wearing his bauta mask, his disguise, and fled—believing it was him, Leonard—engaged in some clandestine, compromising act. Leonard’s jaw tightened. “Did you pursue her?”

“Of course not,” Edward scoffed. “One does not chase hysteria. Besides, she was gone before I could blink. Leave it, cousin. You take everything too seriously.”

He felt the air vanish from his lungs, replaced by a strange, metallic hollowness. The realization seemed to echo inside his ribs.

Edward poured himself another glass of wine, humming some meaningless air, entirely oblivious. Leonard stared, unable to disguise the horror that gathered behind his eyes.

She thought it was me.

The thought repeated with quiet violence, pulsing in time with his heartbeat. That fleeting connection on the terrace, the gloved hand that had trembled in his, had meant something beyond words. Now, it had curdled into misunderstanding, poisoned by chance and disguise.

He swallowed hard, forcing composure, but every instinct rebelled. “Edward,” he began, his tone unsteady, “what precisely did you say occurred in the gardens?”

Edward turned lazily, one hand brushing back his disordered hair. “Oh, nothing of great significance. I told you. A woman saw me and bolted as though she’d stumbled upon a ghost. A treat for the eyes, though, if I recall correctly. The usual sort I’m sure, longing for gossip, no doubt. I daresay she’s already invented a scandalous tale or two for her companions.”

Leonard’s jaw tightened. “And you are certain she recognized you?”

Edward smirked. “Recognized you, rather. I wore your mask, remember? Heaven knows what she thinks she saw but let her chatter. Women thrive on melodrama. It nourishes them better than supper.”

There was laughter in his cousin’s tone, but to Leonard it grated like a violin string tuned too tight.

He turned away, staring at the candlelit ballroom through the tall arched doorway. The revelry continued unchecked—music swelling, skirts swirling, laughter shimmering like mist above the marble. Yet to him, the entire world felt suddenly muted, unreal, a pageant of silhouettes and half-truths.

Isabella’s face rose in his mind. The curiosity in her eyes when she spoke of Venetian frescoes, the soft gravity in her voice when she debated whether art should mirror life or transcend it.

How swiftly admiration had become something perilously near to devotion. And now, by one careless exchange of masks, it had all been undone.

Edward’s words dripped lazily through the haze of his thoughts. “You take this far too seriously, cousin. It was a jest… a moment’s convenience. No harm done.”

“No harm?” Leonard’s voice was quiet, but sharp-edged. “To deceive an entire assembly, to compromise another’s name, to drag mine into your folly, do you call that no harm?”

Edward chuckled, the sound low and indulgent. “My dear fellow, you are young. Overly concerned with honor and appearances. In time you will learn that most reputations are as fragile as soap bubbles, and just as easily replaced.”

Leonard’s hands curled at his sides. “Perhaps that is so for those who live without conscience.”

“Ah, conscience!” Edward mocked lightly, draining his glass. “The inheritance of the naive. You will outgrow it, as all men do.”

Leonard looked at him then, not as cousin, nor as companion, but as a stranger. He wondered how two men could share a lineage and yet diverge so utterly in soul. He saw in Edward the sort of charm that could dazzle a room while rotting at the core, the ease of privilege untempered by responsibility.

He might have spoken further, but the words strangled themselves. To defend Isabella now would be to expose her to speculation. It would invite her name into Edward’s circle of idle mockery.

Worse, to reveal the truth would be to betray his cousin’s confidence, to drag family honor into a scandal that might stretch all the way back to England.

What would she think of me now?

The question whispered through him like a cold current. If she believed him false, faithless even in a single evening’s acquaintance, what right had he to contradict her? He had no claim, no standing to demand her understanding.

To explain would be to admit too much. That her opinion mattered, that she had already become something irreplaceable to him.

He turned abruptly, leaving Edward to his wine, and sought the quiet of the upper gallery. There, the air was cooler, touched by the faint night breeze drifting through open shutters. Below, the ballroom blazed with light, a sea of mirrored motion.

From that height, he saw everything: masks glimmering, jewels flickering like constellations, the laughter of strangers rising in soft waves. It all seemed a cruel parody of the joy he had felt hours before.

He rested his hands on the balustrade, gripping the carved stone until his knuckles whitened. Venice lay beyond, a labyrinth of water and reflection.

The Grand Canal, silvered by moonlight, curved like a living vein through the heart of the city. Somewhere out there, she would be withdrawing with her family, perhaps already determined never to meet his eyes again.

He wanted to find her, to explain. Yet each imagined path led to ruin. To admit that Edward had borrowed his mask would be to confess deceit—not only his cousin’s, but his own complicity.

He had agreed, after all. Reluctantly, yes, but without protest strong enough to absolve him. His silence had woven him into the lie.

He withdrew her handkerchief from his coat pocket and stared. The silk was faintly scented—jasmine, perhaps, or something rarer—a perfume more suggestion than substance. The faint impression of her fingers lingered in the fabric.

It seemed impossible that such a small object could contain the weight of so much feeling.

From below came another ripple of laughter; Edward’s voice again, unmistakable. Leonard closed his eyes. He could not remain there, nor could he confront her tonight. Too much was at stake; too much pride, too much risk.

He descended the marble staircase slowly, each step a negotiation between resolve and regret.

By the time dawn crept through the shutters of his rented apartments, Venice had fallen silent. The canals slept beneath a gauze of mist. The city, emptied of music and revelry, seemed to breathe in long, weary sighs.

Leonard sat at his writing desk, a blank sheet before him, the ink trembling faintly in its well.

He hesitated before setting the pen to paper. What could he say that would not sound feeble or contrived? That he had not been the man she saw? That his cousin’s whim had painted him a liar? The truth itself sounded like invention. Yet to say nothing would seal her misjudgment forever.

He began at last, the words hesitant at first, then flowing with quiet desperation.

My dear Miss Nightingale,

Circumstances most unfortunate have led to a misunderstanding which I cannot bear to leave unaddressed. Believe me when I assure you, I would never willingly cause you distress or invite the shadow of impropriety upon your name…

He paused, the ink still glistening, then folded the note before he could betray too much heart in it. Simplicity, he told himself, was safer.

He summoned a servant and sent the message at once to the Nightingales’ lodgings. The hours that followed stretched endlessly, each one tightening the knot within his chest.

By noon, the reply arrived—not from Isabella, but from the innkeeper himself. The Nightingale party had departed Venice at dawn. Their gondolas had been seen heading toward the railway station. No forwarding address had been left.

For a moment Leonard simply stared, uncomprehending. Then the truth settled with cold precision.

She was gone.

He rose, crossing to the window where sunlight fractured across the canal. Somewhere beneath that golden water, reflections shifted. They were fickle, beautiful, and utterly unreachable. He drew the handkerchief once more from his pocket and held it in the light. The silk gleamed faintly, as though remembering the moon.

His hand closed around it.

To protect his cousin’s secret, he had sacrificed her trust. He told himself it was the right choice—honor demanded it, family demanded it—but the reasoning felt hollow, a moral built on sand.

He had chosen loyalty over love and now stood with neither.

The cloth slipped from his fingers, brushing the floor with a whisper like a sigh.

Would that single deception—trivial, accidental, unmeant—rewrite the course of both their lives?

OFFER: A BRAND NEW SERIES AND 2 FREEBIES FOR YOU!

Grab my new series, "Secrets and Courtships of the Regency", and get 2 FREE novels as a gift! Have a look here!

Hello there, my dearest readers! I hope you enjoyed this sneak peek! Can’t wait to read all of your comments below! ❤️